A footing in Geometric Quantisation

Weekly Meetings: Geometric Quantisation

This set of notes is based off of: https://arxiv.org/pdf/math-ph/0405065.pdf and https://arxiv.org/pdf/1206.2334.pdf

Week 1 - Axel Polaczek

What is the purpose of geometric quantisation? To construct a methodology of taking a classical theory on a manifold and creating a quantum theory. This is done by making use of symplectic geometry (the stage for classical mechanics) and associating to a symplectic manifold a U(1)-principal bundle with connection. Then construction a Hilbert space of states is the space of sections of the associated line bundle.

There are some subtleties and obstructions that will present themselves which will prevent us from constructing such structures for any symplectic manifold.

Symplectic Geometry

We need to have some basic understand of symplectic geometry, so there will be a lot of definitions following:

Definition A pair \((M,\omega)\) consisting of a manifold \(M\) and a two-form \(\omega\) is said to be symplectic manifold if we have that the two form satisfies

- \(d\omega = 0\) (closedness)

- if \(\omega(X,Y) = 0\) for all \(X\in \Gamma(TM)\) then we must have that \(Y = 0\). (non degenerate )

We can also have symplectic vector fields, \[X\in \Gamma(TM)\] if we have that \(\mathcal{L}_X \omega = 0\). Using the interior product, \((i_X \omega) (Y) = \omega(X,Y)\) we can express this condition as: \((i_X \circ d + d \circ i_X)\omega = 0\). Which when combined with the closeness property of the symplectic form, we have that a vector field is symplectic if \((d \circ i_X) \omega =0\)

An important concept is that of a Hamiltonian vector field.

Definition: A function, \(f\) defines a vector field called the Hamiltonian vector field (of \(f\)) \(X_f \in \Gamma(TM)\) which obeys the relation: \(d f = - i_{X_f} \omega\)

Expressing this relationship a bit more fully, we see that \(df (Y) = Y(f)\) by definition of the differential and by the definition of the Hamiltonian vector field we can write this as: \(df(Y) = (- i_{X_f} \omega)(Y) = -\omega(X_f, Y)\). The minus sign seems to be a quirk of Axel’s (the person giving this talk) as most online resources I’ve come across don’t include it. Something to keep an eye on as we proceed, as we will change speakers.

The next structure we need is that of a Poisson Bracket.

Definition: A map \(\{\cdot,\cdot\}: C^\infty(M) \to C^\infty(M) \to C^\infty(M)\) is called the Poisson bracket of the symplectic form \(\omega\) if we have that \(\{f,g\} = i_{X_f}i_{X_g} \omega= - \omega(X_f,X_g)\)

This is called the natural Poisson structure of a symplectic manifold.

Proposition: A function \(g\) is constant along the integral curves of the hamiltonian vector field \(X_f\) if and only if \(\{f,g\} = 0\).

Proof: Take \(\gamma:[0,1] \to M\) to be the integral curve of \(X_f\). So we can then look at \(\frac{d}{dt} g(\gamma(t)) = X_f(g(\gamma(t)))\) (which is just definition of an integral curve), then we can examine the right hand side as the following: \[ X_f(g(\gamma(t))) = d(g\circ\gamma)(t) (X_f) = i_{X_f} d(g\circ \gamma)(t) \] We then take the hamiltonian vector field associated to \(g\), and we can express \(dg = -i_{X_g}\omega\) this as: \[ X_f(g(\gamma(t))) = i_{X_f} (dg \circ d\gamma) (t) = - i_{X_f} (i_{X_g} \omega) (\gamma(t)) = -\{f,g\} (\gamma(t)) \] As this holds for arbitrary values of \(t\) this must hold along the entire curve \(\gamma\).

Another handy result is that \(X_{\{f,g\}} = - [X_f, X_g]\), which can be shown if we invert the statement above for the Lie derivative interns of the interior and exterior product. To get that \(i_{[X,Y]} =[\mathcal{L}_X,Y]\).

Also, as we have that \(d\omega = 0\) then by Poincare lemma we have that \(\omega = d\theta\).

Time for the classic example:

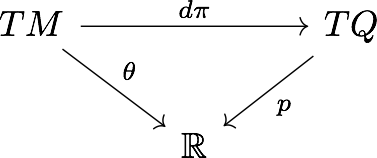

Examples: Take the manifold to be the total space of the cotangent bundle \(M =T^*(Q)\) over some manifold \(Q\)? (I think we just treat \(Q\) as a vector space, but I’m not sure where this becomes important if at all). So then points in this space are of the form \(m = (q,p) \in M\) and we can form a bundle structure over \(Q\) by taking projection onto the first coordinate \(\pi:M \to Q\) (so we are just taking the cotangent bundle over \(Q\)). We need a map \(\theta: TM \to \mathbb{R}\) (i.e. \(\theta \in \Omega^1(M)\)) such that the following diagram commutes

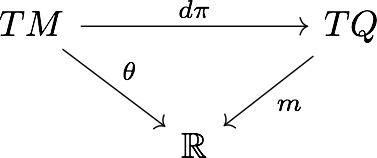

Where \(p:TQ \to \mathbb{R}\) is what exactly? My notes from the time don’t say, but lets figure this out. Given a point \(m\in M = T^*Q\) we know that it gets mapped to \(q\) under the map \(\pi\). Alternatively we can view \(m\) as a map from \(T_qQ \to \mathbb{R}\) as its a one-form after all. Which in Axels notes must be the map \(p\) above, alternatively I’ll write it as \(m\) below.

So what is the combination \(m\circ d\pi\) , it acts on an element of \(TM\) corresponding to the point \(m\in M\) and sends it to \(\mathbb{R}\). So it’s a map from \(T_mM \to \mathbb{R}\) which is means in the diagrams above, we need to put a specific on \(\theta = \theta_m\). Then we vary \(m\) over the entire manifold and see that the formula holds.

In terms of coordinates we have that \(\theta = p_i dq_i\) where \(p = p_idx^i\) and \(q_i:M \to \mathbb{R}\) are the coordinates in a local chart of \(M\) treated as functions on \(M\).

Example: Take \(M = T^*\mathbb{R}\), with points \((q,p) = m\in M\) and \(\omega = dp \wedge dq\) and \(dH = -i_{X_H}\omega\) . We can write any vector field in terms of it’s components \(X_H = X^p_H \frac{\partial}{\partial p} + X^q_H \frac{\partial}{\partial q}\) . By looking at the definition of a Hamiltonian vector field we have \[ dH(Y)= -i_{X_H} \omega(Y) = - \omega(X_H,Y) = -(X^p_H dq(Y) - X^q_H dp(Y)) \] so that \(dH = - (X^p_H dq - X^q_H dp)\), but we also have that \(dH = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p} dp + \frac{\partial H}{\partial q} dq\). So we have that $X^p_H = - $ and \(X^q_H = \frac{\partial H}{\partial p}\) and so combining we get: \[ X_H = - \frac{\partial H}{\partial q}\frac{\partial}{\partial p} + \frac{\partial H}{\partial p}\frac{\partial}{\partial q} \]

Quantisation

What we want is a map \(\mathcal{Q}: Obs \to End(\mathcal{H})\) which maps us from the space of classical observables on our symplectic manifold to some operators on a Hilbert space. The space of observables is just the algebra of functions \(C^\infty(M)\). We want this map to follow some general rules

there was a fair bit of discussion about whether or not we want this map to satisfy all of the requirements or not. I’m sure it will come up again later

- Q1: \(Q(1) = Q_1 = id\) , so the identity is mapped to the identity.

- Q2: \(Q_{\alpha f + g} = \alpha Q_f + Q_g\) , so the map preserves the linear structure.

- Q3: \([Q_f, Q_g] = i\hbar Q_{\{f,g\}}\) , this is the condition that required all the background on symplectic manifolds, but you can see that it maps the symplectic structure to a commutator. We will see why this is important later I guess.

There was one other condition and it caused some disagreement between the audience of the meeting.

-

Q4: For \(\phi: M^{(1)}

\to M^{(2)}\) such the \(\phi^*\omega^{(2)} = \omega^{(1)}\) and for

\(f\in C^\infty(M^{(2)}) = Obs^{(2)}\)

we want

- \(f\circ \phi \in Obs^{(1)}\)

- \(\exists U_\phi :\mathcal{H^{(1)}} \to \mathcal{H^{(2)}}\) such that \(Q^{(1)}_{f\circ \phi} = U^*_\phi Q^{(2)}_f U_\phi\)

These are statements about irreducibility. Which I understand to be that the Stone vonNeumann theorem tells us that there is unique (up to unitary equivalence) representation that is irreducible (I.e. that map \(Q\) is an irreducible representation of \(Obs\)) that satisfies the standard canonical commutation relations. However, the way it’s formalised above is supposed to exists for a general manifold, even when the split of \(M = T^*Q\) (where \(Q\) is some general symplectic manifold now instead of a vector space as above) into global coordinates \((q,p)\) doesn’t exist. However, it’s not clear that this is true to me.

Week 2 - Axel Polaczek

We examine the above example, where \(M = T^*Q\) for \(Q = \mathbb{R^d}\). Then we can take \(\omega = d\theta\) where \(\theta\) is known globally so we can write it as above \(\theta = p_i dq^i\). In this case we have an expression for the map \(Q\). \[ Q_f = - i \hbar X_f - \theta(X_f) + f \] Where the Hilbert space in question is \(\mathcal{H} = L^2(M)\), where the norm is given by the inner product \(\langle \phi,\psi \rangle = \int_M \omega^n \phi^* \psi\) or something similar. (I think d = 2n but not 100% sure).

We then can check that this map satisfied Q1 - Q4.

However, in the general case of a symplectic manifold \(Q\). We can’t choose global coordinates for \(Q\) or \(M = T^*Q\). However by Darboux theorem we can always choose a covering of \(Q\) such that in each coordinate patch \(\omega = dp_i \wedge dq_i\) and so that we can express the symplectic potential in that patch as \(\theta = p_idq_i\).

So if we take two charts \(U_a, U_b\), take \(\theta\) to be defined on \(U_a\) and \(\theta^\prime\) to be defined on \(U_b\) and look at \(\omega\) on the overlap of \(U_a \cap U_b\). Then we have that \(\omega = d\theta = d\theta^\prime\). So we know then that \(\theta = \theta^\prime + du_{ab}\) and the functions \(u_{ab}\) depends on the coordinate patches in question.

As the definition of \(Q\) above depends on the potentials \(\theta\) we should examine how the terms in the expression above differ in the different coordinate patches. \[ \theta(X_f) - \theta^\prime(X_f) = du(X_f) = X_f(u) \] We can then write \(X_f(u)\) as the following expression involving operators \(e^{-u}\) and \(e^u\). We do this as we want to relate the two expression of \(Q\) to each other via unitary operators and this step will help us do that. \[ X_f(u) = -e^u X_f e^{-u} \] Then we can render the expression \(Q_f\) in the chart \(U_a\) and use the relation for the potentials. \[ \begin{align} e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar}} Q_f^a e^{-\frac{u}{i\hbar}} \phi &= e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar}} \left( -i\hbar X_f - \theta(X_f)+f\right) e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar} } \phi\\ &= e^{- \frac{u}{i\hbar}}\left( -i\hbar X_f + f - \theta^\prime(X_f) - X_f(u) \right)e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar}} \phi\\ &=e^{- \frac{u}{i\hbar}} \left( -i\hbar X_f + f -\theta^\prime(X_f) - X_f(u) \right)e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar}} \phi\\ &=\left( i\hbar e^{- \frac{u}{i\hbar}}X_f e^{-\frac{u}{i\hbar}} + f - \theta^\prime(X_f) - X_f(u) \right)\phi \end{align} \] As \(X_f(u)\) is just a function, the exponentials can commute with it. However, for the \(-ihX_f\) we need to act the vector field. \[ \begin{align} -i\hbar e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar}} X_f (e^{-\frac{u}{i\hbar}}\phi) &= -i\hbar e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar}} X_f (e^{-\frac{u}{i\hbar}}) \phi + -i\hbar e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar}}e^{-\frac{u}{i\hbar}} X_f (\phi) \\ &= (+X_f(u) -i\hbar X_f) \phi \end{align} \] So substituting this into the expression above gives us that \[ e^{\frac{u}{i\hbar}} Q_f^a e^{-\frac{u}{i\hbar}} \phi = \left(-i\hbar X_f + f -\theta^\prime(X_f)\right)\phi = Q^b_f \phi \] ### Complex Line Bundles

We know switch gears, and view all of the above construction as being data in an Hermitian complex line bundle with connection/covariant derivative with the symplectic form used so heavily above, being related to curvature of the covariant derivative.

Given a 1 dimensional complex vector bundle \(\mathbb{L} \overset{\pi}{\longrightarrow} M\), let \(\varphi_u: \pi^{-1}(U) \to U\times \mathbb{C}\) be the local trivialisations and on the intersections \(U_{\alpha \beta} = U_\alpha \cap U_\beta \neq \emptyset\) let \(g_{\alpha\beta}: \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}\) be the transitions functions such that: \[ \begin{align} \varphi_\alpha^{-1} \circ \varphi_\beta : &U_{\alpha \beta} \times \mathbb{C} \to &U_{\alpha \beta} \times \mathbb{C}\\ & (m,\phi_\beta)\mapsto & (m,g_{\alpha\beta} \psi_\beta ) \end{align} \] And such that they satisfy the cocycle conditions for triple intersections \(U_{\alpha\beta\gamma}\):

\(g_{ab}g_{bc}g_{ca} = 1\), \(g_{\alpha \beta}g_{\beta \gamma} = g_{\alpha \gamma}\). \(g_{\alpha \alpha } = 1\) and also \(g_{\alpha\beta} = \frac{1}{g_{\beta \alpha}}\).

If we view \(exp(\frac{u_{ab}}{i\hbar}) = g_{ab}\) as transition functions. Then the fact that transition functions have to satisfy the cocycle condition that \(g_{ab}g_{bc}g_{ca} = 1\), then we need that \(u_{ab} + u_{bc} + u_{ca} = n_{abc}\in \mathbb{Z}\). Which is called the integrability condition or prequantisation condition.

To this line bundle we can also have a covariant derivative, which is a prescription to “differentiate” sections of a vector bundle along the direction of a vector field.

Definition: A covariant derivative on \(\mathbb{L} \to M\) is a map \(\nabla: \mathfrak{X}(M) \times \Gamma(\mathbb{L}) \to \Gamma(\mathbb{L})\) such that the following conditions are true:

- (function linearity) \(\nabla_{fX} (\psi) = f \nabla_X(\psi)\)

- (Leibniz relation) \(\nabla_X(f\psi) = f \nabla_X(\psi) + X(f) \psi\)

where \(f\in C^\infty(M,\mathbb{C})\), \(X\in \mathfrak{X}(M)\) and \(s\in \Gamma(\mathbb{L})\).

We now just need to construct the Hermitian structure such that it is doesn’t not conflict with the connection.

Definition: A complex line bundle is called Hermitian if there exists local sections of the line bundle \(\{ e_\alpha: U_\alpha \to U_\alpha \times \mathbb{C} \}\) which obey the following relationship: \[ e_\alpha = |g_{\alpha \beta}|^{-2} e_\beta \] where \(g_{\alpha\beta}\) are the transition functions of the line bundle. We can then define a fibre-wise inner product of sections in the following way: \[ (\phi, \psi)_m = e_\alpha(m) \bar{\phi}_\alpha(m) \psi_\alpha(m) \]

In order for this Hermitian structure to be compatible with the connection we require the following relation: \[ X((\phi,\psi)_m) = (\nabla_X\phi, \psi)_m + (\phi, \nabla_X \psi)_m \] for every point \(m\in M\).

One last definition is that of the curvature of a covariant derivative:

Definition: The curvature of a covariant derivative is given by \[ R^\nabla(X,Y) = \nabla_X\nabla_Y - \nabla_Y \nabla_X - \nabla_{[X,Y]} \]

This is a map from \(\Gamma(\mathbb{L})\) to itself, i.e. \(\in End(\Gamma(\mathbb{L}))\).

Making the link

In a local chart \(U_\alpha\) we take the covariant derivative to have the following form: \[ \nabla_X \psi_\alpha = \left( X - \frac{i}{\hbar}\theta_\alpha(X)\right) \psi_\alpha \]

Then we can calculate the curvature:

\[\begin{align} R^\nabla(X,Y)\psi_\alpha =& (X - \frac{i}{\hbar}\theta_\alpha(X))( Y - \frac{i}{\hbar}\theta_\alpha(Y)) \psi_\alpha \\ &- (Y - \frac{i}{\hbar}\theta_\alpha(Y))(X - \frac{i}{\hbar}\theta_\alpha(X)) \psi_\alpha \\ &- ([X,Y]\psi_\alpha - \frac{i}{\hbar}\theta_\alpha([X,Y]))\psi_\alpha\\ =& XY\psi_\alpha - \left(\frac{i}{\hbar} X\theta_\alpha(Y) + \frac{i}{\hbar} \theta_\alpha(X) Y\right)\psi_\alpha - \frac{1}{\hbar^2}\theta_\alpha(X)\theta_\alpha(Y) \psi_\alpha \\ &- YX\psi_\alpha + \left(\frac{i}{\hbar} Y\theta_\alpha(X) + \frac{i}{\hbar} \theta_\alpha(Y)X \right)\psi_\alpha + \frac{1}{\hbar^2}\theta_\alpha(Y)\theta_\alpha(X) \psi_\alpha \\ & - [X,Y] \psi_\alpha + \frac{i}{\hbar} \theta_\alpha([X,Y])\psi_\alpha\\ =& XY\psi_\alpha - YX \psi_\alpha + \frac{i}{\hbar}\left( Y\theta_\alpha(X)- X\theta_\alpha(Y)\right)\psi_\alpha - \frac{i}{\hbar}(\theta_\alpha(X)Y - \theta_\alpha(Y) X) \psi_\alpha \\ &- [X,Y]\psi_\alpha + \frac{i}{\hbar}\theta_\alpha([X,Y])\psi_\alpha \end{align}\]

Where the terms of the form \(\frac{1}{\hbar^2} \theta(X) \theta(Y)\) cancel as \(\theta_\alpha(X)\) is just a function, so we can commute the terms and cancel them. The following terms require some investigation: \[ \begin{align} (Y\theta_\alpha(X)- X\theta_\alpha(Y))\psi &= Y (p_i X(q^i)\psi) - X(p_i(Y(q^i)\psi)\\ &= p_i (Y(X(q^i)\psi) - X(Y(q^i)\psi)) + Y(p_i)X(q^i)\psi - X(p_i)Y(q^i)\psi\\ & = p_i(Y(X(q^i))\psi) + p_iX(q^i)Y(\psi) - p_i(X(Y(q^i)))\psi - p_iY(q^i)X(\psi) \\ & \qquad+ Y(p_i)X(q^i)\psi - X(p_i)Y(q^i)\psi\\ & = \big(p_i(Y(X(q^i)) - p_i(X(Y(q^i))) + p_iX(q^i)Y - p_iY(q^i)X\big)\\ & \qquad + Y(p_i)X(q^i)\psi - X(p_i)Y(q^i)\psi\psi \end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align} \theta_\alpha([X,Y]) &= p_i dq^i([X,Y]) =p_i (X(dq^i(Y)) - Y(dq^i(X)))\\ &= p_i(X(Y(q^i)) - Y(X(q^i))) \end{align} \]

\[ \theta_\alpha(X)Y - \theta_\alpha(Y)X = p_iX(q_i)Y - p_i Y(q_i)X \]

From these formula’s we can see that \[ Y\theta_\alpha(X) - X\theta_\alpha(Y) = -\theta_\alpha([X,Y]) + \theta_\alpha(X)Y - \theta_\alpha(Y)X + + Y(p_i)X(q^i)\psi - X(p_i)Y(q^i)\psi \] Substituting this into the expression for the curvature we find that \[ \begin{align} R^\nabla(X,Y)\psi_\alpha &= \frac{i}{\hbar} \left( Y(p_i)X(q^i)\psi - X(p_i)Y(q^i) \right)\psi \\ &= \frac{i}{\hbar}\left(dp_i(Y) dq^i(X) - dp_i(X) dq^i(Y)\right)\\ &= \frac{i}{\hbar} (dp_i\wedge dq^i (Y,X))\\ &= - \frac{i}{\hbar} \omega(X,Y) \end{align} \] Note that in the set of notes we are following, they define the curvature to be \(i\) times the curvature I have defined. This doesn’t seem to be standard so I’ve changed it and now our curvature is complex, which isn’t so pleasant. However, if the other set of notes, approaches the topic in this way I’ve laid out here. It’s just worth pointing out that there is a difference.

So we have prequantised our symplectic manifold. We have found a methodology to form a Hermitian complex line bundle with connection over the same base space such that the symplectic form is given by the curvature of the connection. To fully quantise, we need to construct a procedure to associate a Hilbert space to every point in the base space. That’s the next step which Hans Nguyen will present.

Week 3 - Hans Nguyen

This next two lectures will explore the notion of polarisation and half-densities. This is needed because of the fact that the inner product given by the symplectic form produces a Hilbert space that too big for physics. Which means that in the cases we know how to quantise, it produces too many variables for the wavefunction to be dependent on. I believe more mathematical terminology for this is that the representation isn’t irreducible. From the book by Woodhouse on Geometric Quantisation states that in the classical case of the cotangent bundle of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) you end up with wave functions on \(\mathbb{R}^{2n}\), which is double the dimension we want from Quantum mechanics. And from quantising coadjoint orbits, you find the representation is irreducible. Both of which are fixed by Polarisation.

We need to form a Hilbert space, which means we need an inner product on the complex line bundle defined above (called the prequantum line bundle).

Definition: Given a Hermitian line bundle \((\mathbb{L} \to M, \nabla, (,)_{\pi^{-1}(x)})\) we can define an inner product of sections \(s,s^\prime \in \Gamma(\mathbb{L})\) in the following way: \[ \langle s, s^\prime \rangle = \int_M (s,s^\prime) \omega^n \] Where we would need to use partitions of unity and likewise techniques to take the fibrewise inner product to a global expression.

We can define the square integrable sections, \(L^2(\Gamma(\mathbb{L}))\) as being norm completion of the set of sections \(s \in\Gamma(\mathbb{L})\) that satisfy \(\langle s,s, \rangle < \infty\). This space \(L^2(\Gamma(\mathbb{L})\) is called the prequantum hilbert space.

Example: Lets have \(Q = \mathbb{R}\) so the phase spaceis given by \(T^*Q = \mathbb{R}\times \mathbb{R}\) with symplectic form \(\omega = dq\wedge dq\) with p and q living in their own copy of \(\mathbb{R}\). The prequantum bundle (i.e. the hermitian line bunde) is given by: \(T^*\mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{C} \to T^*\mathbb{R}\) is the trivial bundle. Then the inner products are all defined globally, so we find that \(\mathcal{H} = L^2(T^*\mathbb{R}, \mathbb{C}) = L^2(\mathbb{R}^2, \mathbb{C})\) which is not correct as we want the wave functions to just be dependant on the position.

Lets get to Polarisation:

Polarisation

A polarisation is a choice of half of the variables that is consistent with all the structures previously defined. To make this into precise mathematics we need to define some new notions (new to us, not new new).

Definition: A Lagrangian subspace \(\Lambda\) of a symplectic vector space \((V, \omega)\) is the collection of elements in \(V\) such that:

- \(\omega(V,v^\prime) = 0\) for all \(v, v^\prime \in V\). This is known as the isotropic condition

- \(\Lambda\) is a maximal isotropic subspace (as in the above notion of isotropy).

It can be shown (in general) for Lagrangian subspaces that they have dimension \(\frac{1}{2} dim(V)\).

So the aim is to prescribe a Lagrangian subspace to every tangent space in a consistent way.

Definition: A Real polarisation on \((M,\omega)\) is a subbundle of the tangent bundle \(\mathcal{F}\subset TM\) such that every fibre is a Lagrangian subspace of the tangent space and such that the commutator of local sections is also a local section. Summed up in maths:

- \(\mathcal{F}_x \subset T_xM\) is Lagrangian. This is referred to as the Lagrangian conditions

- if \(X,Y\) are local sections (i.e. \(U\subset M\) then \(X\in \Gamma(\mathcal{F} \to U)\) so \(X(x) \in \mathcal{F}_x\)). This is referred to as the Integrable condition.